In the previous post, I had written of the seclusion of the cave monasteries in Ajanta. In this post, I write about the exact opposite – the open, easily found monasteries between the Arabian Sea in the west and Ajanta in the east. As a traveler with a bias towards history, if I plot the various Buddhist monasteries of Maharashtra that I have visited on a map, there is an interesting observation that I make which, after reading various literature and historical studies, seems to have a clear explanation.

Starting with Kanheri in Mumbai, there is Karla (8km from Lonavala), Panduleni (Nashik), Ellora (about 10 caves) and finally Ajanta. (There are many more like Junnar, Aurangabad, Bhaja, etc. but since I have not yet visited them I will not talk about as yet. )

These five spots, when plotted on the map, reveal that they are on two lines going east from the sea – one going North East, the other South East. They run in the same direction as two major highways which emanate from Mumbai – NH3 and NH4. The ASI informs us that this is not coincidence. In effect, there were ancient trade routes from the port town of Sopara (present day Nalla Sopara) which connected with the great cities inland include Pratishthana (modern day Paithan) which was the capital of the Satavahanas who reigned between the 3rd century BCE to 2nd century CE. The immediate conclusion is that, like the serais on the Silk Route, these monasteries were specially constructed on these trade routes and served as rest places for traders.

The Western Ghats is filled with over a 1000+ such sites. And the story seems to be same for all of them. Here is an excerpt from Sukumar Duut’s Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India.

The Deccan Trap is comparatively soft. If the monks wanted retreats on the mountain-sides, the wealthy monks would not be wanting to build them. There were winding passes and traffic for the flow of internal trade and traffic. Places, not to distant from these routes yet a suitable remove to be secluded were naturally favoured.

Buddhism had its golden period once Ashoka embraced and spread the Dhamma through his numerous rock edicts. As it became the religion of the people, Buddhist cave monasteries became not just residences for the practicing monks but also places which offered a number of services to the public who were of diverse background – traders, noblemen, commoners. The inscriptions in the various monasteries suggest that apart from kings, wealthy traders and noblemen donated to their excavation and construction of the various viharas and chaityagrihas. In doing so, they thus sponsored the best craftsmen to conjure up all the classic sculptures and art that you can see in these monasteries.

So with this in mind, one can now look at the different embellishments done at these caves and try to imagine how they may have served both the monk looking for seclusion and the weary traveler looking for rest and recreation (and some mental happiness).

First of all, the size of the prayer hall (chaityagriha) at Kanheri and Karla are among the largest of all the cave monasteries that have been found. With a wide courtyard in front, this particular facility is well suited for large gatherings to assemble and mingle freely with ample space for everyone.

The chaityagriha of Kanheri

For the seclusion of the inmates i.e. the residences of the monks, once you turn round the curve and go deep into the hill, you see a whole warren of caves. They are distinctly invisible from the road below and even from the main prayer hall, they require a little effort in climbing up. Thus both the needs are met. Similar concepts can be found in design of many modern day educational complexes where the main classrooms and office buildings are easily accessible from the road while the rooms for the faculty and the students hostels are hidden somewhere at the back.

The viharas (residences) of the monks at Kanheri

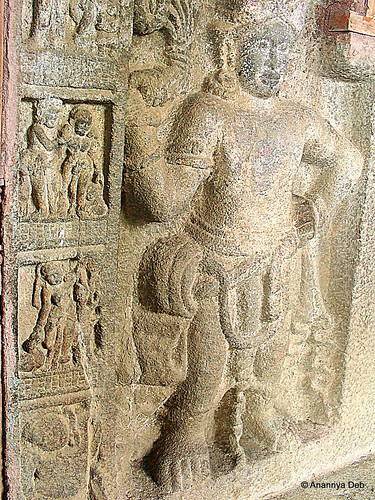

And what about the ornate artworks? Almost every cave has a recorded history (through inscriptions) of excavations and modifications ranging from 500 years to over 1000 years. During this period, Buddhism also saw a transformation from the more austere Hinayana to the more extravagant Mahayana where the likeness of the Buddha could now be carved out in various forms. Just like the Renaissance period in art came from the need to illustrate and bring to life stories from the holy book, the Mahayana period saw craftsmen bring out the different stories, themes and ideas of the Buddha and Buddhism in stone form (and mural work in the case of Ajanta).

Sculptures at Panduleni (Nashik)

Sculptures at Karla

Cave 1 in Ajanta – the iconic paintings flanking the Buddha

As a history buff, making this “trail” albeit serendipitously provides a nice sense of achievement for me. Instead of randomly visiting discrete places, there is a nice thread emerging out of these visits. There are some trails which I have been following quite consciously – like visiting various imperial capitals in the Deccan peninsula and so on. But this particular discovery for myself feels good.

2 thoughts on “History Travel – The Buddhist Cave Monasteries of Maharashtra”