At any given point in time, in Mumbai, there are multiple eras / generations / timelines existing simultaneously in the city, in a form that DD Kosambi called the “living prehistory”. Here are ten pictures from different parts of the city (and to be fair, one has to include a few areas outside the present day municipal limits).

1. The Mauryan era (Kanheri Caves, 2nd century BCE onwards)

Buddhism demanded detachment of all material pleasure. This meant settlements in natural environs like caves suitably modified to house thousands of monks. The infrastructural needs for monks were limited – a large prayer hall, various platforms for discourse, dormitories for sleeping, a common assembly area for meals and cisterns of water for all the usual ablutions. Having a river or any water body nearby was an added advantage.

Kanheri Caves has all of these. Over 120 caves are scattered over the entire hill in the middle of what is now the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Various inscriptions on the walls of the caves date the caves from 2nd Century BC right up to the 10th or 11th century CE. The caves are located on an ancient trade route heading towards the port town of Sopara, a prosperous centre during the Mauryan era.

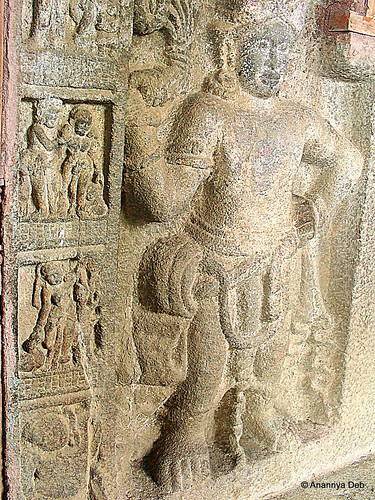

2. The Rashtrakuta Era ( Elephanta Caves / Island , 6th – 8th century CE)

The Elephanta Caves as a tourist landmark is quite a cliche. It’s quite boring beyond a point. I have been there three times now in the last ten years and I think I have had enough. But that is because of overkill. The sculptures themselves are magnificent. They recall very vividly Cave 29 in Ellora, also built around the same time under the Rashtrakuta kings.

3. The Shilhara era (Banganga / Walkeshwar , 12th Century)

A tourist inscription at the Banganga tank retells a story from the Ramayana. Our three protagonists, having wandered here, were resting on the hill in Bombay island. Sea water is salty. So for looking for fresh water to drink, Lakshman did the old trick – he fired an arrow into the ground. And a spring erupted with fresh water. Since the only source of fresh water known to man at that time was the Ganga, it was believed that this spring was connected to the Himalayan river, thousands of miles away. Hence, the spring was named Banganga. The tank structure per se dates back to the 12th century during the reign of the Silhara kings. They were the ones who brought in settlers from the interiors and soon, apart from the fisherfolk, there were all kinds of people from all the four castes doing their respective duties. The descendants of those early settlers – the Pathare Prabhus, the GSBs, etc. – are still amongst the key influencers of the city.

Today, Banganga continues to house some of those ancient structures in the form of gates, pillars, the occasional memorials and inscriptions. There does not seem to be much change in the routines of the various temples. Of course, modernity has allowed for loud speakers and musical accompaniments made up of mobile phone ring tones.

In this picture, like in any archaeological excavation, one can see the layers of time in the different structures – from very ancient steps to the more modern high rises.

4. Sultanates of Gujarat & Deccan era (Mahim – Worli, 15th century)

The island of Mahim, along with the other islands, came under Islamic rule for about 200 years. In the 14th century, the Sultan of Gujarat defeated the Shilharas and took over the island of Mahim. All the islands that made up the Bombay archipelago were ideal for shipping and all those involved in the west coast maritime activities tried to gain a foothold in one or more of these islands. The Sultan of Gujarat was one contender. The Bahmani sultanate was another. There was the famous Ahmad Shah (Gujarat / Ahmadabad) versus Ahmad Shah (Bahmani / Ahmadnagar) battle over Mahim in the 15th century. The Gujarat side won. In joy, Ahmad Shah of Gujarat built a number of mosques on land and on sea.

5. Portuguese era (Bandra Fort, 17th century)

Castella de Aguada was built in the 17th century by the Portuguese as a watering hole for ships (there were a number of fresh water springs here) and later as a bastion against the British who, apart from territorial victories through local battles, had taken over the other islands of Bombay following the marriage of Charles II. The Portuguese had earlier, in 1517, taken over the Mahim fort from the Sultan of Gujarat. The St Michael’s Church in Mahim dates to this period. As the seven islands of Bombay were handed over to the British, the Portuguese retreated northwards to Bandra, Malad and Bassein (Vasai) where it continued to reign for another century or so.

From Dadar right up to Vasai, one can trace a whole line of extant churches built in the 16th and 17th centuries by the Portuguese. Of course, their legacy also lives in the ubiquitous vada-pav where both the potato and the bread were introduced by them.

6. British era (St Thomas Cathedral, 18th century)

When a power establishes themselves in any place, they show their supremacy by building a religious institution. The Hindu empires built all those temples in South India; the Mughals built all kinds of mosques at various places after victories in battles or the like. The British did the same in every city they took over. St Thomas Cathedral in 1716 was the first Anglican church in India and it capped the complete control of Bombay that British now secured for themselves.

The first church, a monumental one, obviously becomes a landmark. And so it lends itself to Churchgate, the railway station complex that stood outside the fort gate facing the church.

7. Gandhi & Freedom Struggle (Mani Bhavan, early 20th century)

The two storey house originally belonging to Revashankar Jhaveri is now part of a network of Gandhi memorials across the country which includes the Sabarmati Ashram and places outside India as well.

The room in which Gandhi stayed in, like all the other memorials, is arranged in the same way – mattress or rug on the floor, a writing table with paper, quills, blotting paper, etc, a spinning wheel on the side and other small stationery items. You will find this arrangement in Sabarmati, at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune, in fact anywhere and everywhere that Gandhi stayed in.

8. The Marathi Manoos era (Shivaji Park, 20th century)

Open spaces are rare in Mumbai. So the existing open spaces have high emotional value. Shivaji Park, like similar features in other major cities, has been the hub of both social and political movements in Mumbai. While the maidans of South Mumbai are associated with the British, Shivaji Park, even though it dates back to 1920s, was always associated with, first, the local nationalist movement and later, the Maharashtra movement. Back in the 1950s, this ground was the venue of meetings and demonstrations related to the creation of the Marathi speaking state. Because of that legacy, the May 1st (Maharashtra Day) parades and celebrations are held in Shivaji Park and not anywhere else.

9. The Bombay Talkies Era (Maratha Mandir, 20th century)

The cinema halls of south and central Mumbai reflect the many evolutions in the city – the movement of people to the northern suburbs leading to lesser patronage, the rising inflation leading the asynchronous economics where the extant pre-independence era monthly rentals from these old properties don’t even cover the cost of a single show, the flux of soft core regional language movies which keeps ever increasing migrant population made up of taxi drivers and restaurant waiters happy. Some of these cinema halls have, of course, made their sorry state into a tourist attraction.

10. Vertical Era (Mumbai Skyline, 21st Century)

The recent freeing up of FSI means builders can go higher and higher. Not just buildings, even roads and transportation services are going above ground.

I will update this post with new pictures from further explorations of Mumbai one year later