This extremely small town (or large village) with a population of less than 5000 people has this one large Shiva temple built in the 9th century CE. Most vacationing people will simply ignore this and instead carry on towards Jog Falls. Which is fine. But for those who like to explore history on their travels, a short detour to this village is worth it.

As George Moraes in his Ph.D thesis work called The Kadamba Kula writes

“The History of the Kadambas is the history of one of the most neglected, though in its own days one of the most influential, of the dynasties that held sway over the Dekkan (sic).”

The news of the city had reached Ptolemy as well and we can find the town “Banauasi” in his Geographic works. During the third Buddhist Council hosted by Emperor Ashoka, a Buddhist monk Rakkhita was deputed to this town. Obviously, as George Moraes says, it must have been an important centre for someone to be specially sent for spreading the word. And about 900 years later, in the 7th century CE, Huien Tsang mentions visiting this place (called Konkanapulo) and finding over 100 monasteries (or sanghramas) with over 10,000 priests. It is believed that with Banavasi as the base, Buddhism spread to the Konkan and other parts of Karnataka.

The Aihole inscription describes Banavasi as a city “whose wealth rivaled the gods” and then proceeds to explain how Pulakesin II of the Badami Chalukyas vanquished the Kadambas of Banavasi.

Banavasi is located in north-western Karnataka, about 120 kilometres south-west from Hubli. To its west lies the Shravati Wildlife Sanctuary up in the Western Ghats which also is the home of the highest waterfall in India, Jog Falls. The town lies on the banks of the Varada river. Like most cities across the world, this city was also established on the banks of a river. In this case, it is the Varada river which is a rain fed river rising in the Western Ghats and flowing down the slope eastwards. The Aihole Inscription mentions that the river encircled a fortress and there were birds in the river which were trained to alert the soldiers in the fortress in case they were attacked. Pulakesin II of the Chalukyas was still able to defeat them and the Aihole Inscription carries on about his greatness. Being rain fed and with a number of hydro-electric dams built along its course, there is not much water left in the river, especially in November.

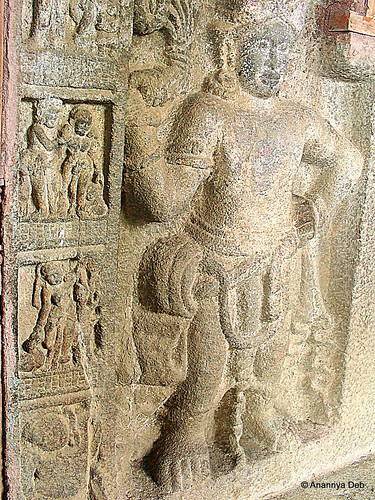

The Madhukeshwara temple is dated to the 9th century CE when the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani held sway over the land. But this temple may have been built over earlier structures as some of the inscriptions tell. Also there are various sculptures that depict different styles, namely the Kadamba, the Chalukya and later the Vijayanagara style.

Each of these styles are unique and the uniqueness is usually palpable. The main areas to focus when looking for uniqueness are a) the shikhara / vimana b) the general plan and c) the lesser number of sculptures. The Kadamba shikhara is typically a pyramid with stepped layers rising and tapering to the peak (see the picture above). You will also find Kadamba architecture in Belgaum, Belur, Halsi and Goa and other surrounding areas.

Exquisite stone work is on display like most other places in peninsular India. However, unlike the artwork in Hampi or Kanchipuram or Ellora or Pattadakal, the sculptures are extremely measured. There are sculptures of Nandi, elephants, warriors, gods and goddesses but each piece of sculpture has a lot of breathing space around it and often there are walls with nothing on it providing some relief.

I visited this town in 2013 in November. I took a state transport bus from Hubli to Sirsi, a 100km ride which took about 2 hours and a bit. From Sirsi, I took another state transport bus, but a very well decked tourist oriented bus to Banavasi, a 23 kilometre ride which took another 30 minutes. I started in from Hubli at 10:15am and I was in Bnavasi by 1.15, waiting time included. I spent 1 hour there walking around, exploring the temple and the village houses all around. By the time I finished, the next bus had arrived from Sirsi and I could take the same bus back and be on my way to Gokarna which was my main destination.

The whole village can be covered in a nice slow 30-minute walk. One passes through small institutes of art and culture including a Yakshagana theatre group. Today, there is a certain charm to this town. The old temple continues to conduct its daily rituals and hosts various festivals as per schedule. There are families coming over, one or two on a normal day, a few more on the weekend and a little more on religious holidays. But, it is a quite unassuming place. There is a resort there as well, on the banks of the river, and it advertises trips to the Jog Falls and the neighbouring forests.

Personally, the 1 hour I spent there was enough for me. It gave me what I wanted, a glimpse of what prosperity was in the first millennium and also a living proof of how a place goes into decline and fall once the political powers disappear. of course, I could tick off another important historical location in Peninsular India from my personal travel list